I’m not a Warhammer player, but…

…I unironically like the old Warhammer 40K universe depictions and canon. You know, the Rick Priestley, John Blanche era. Where everything was bad, grimy, gloomy and evil.

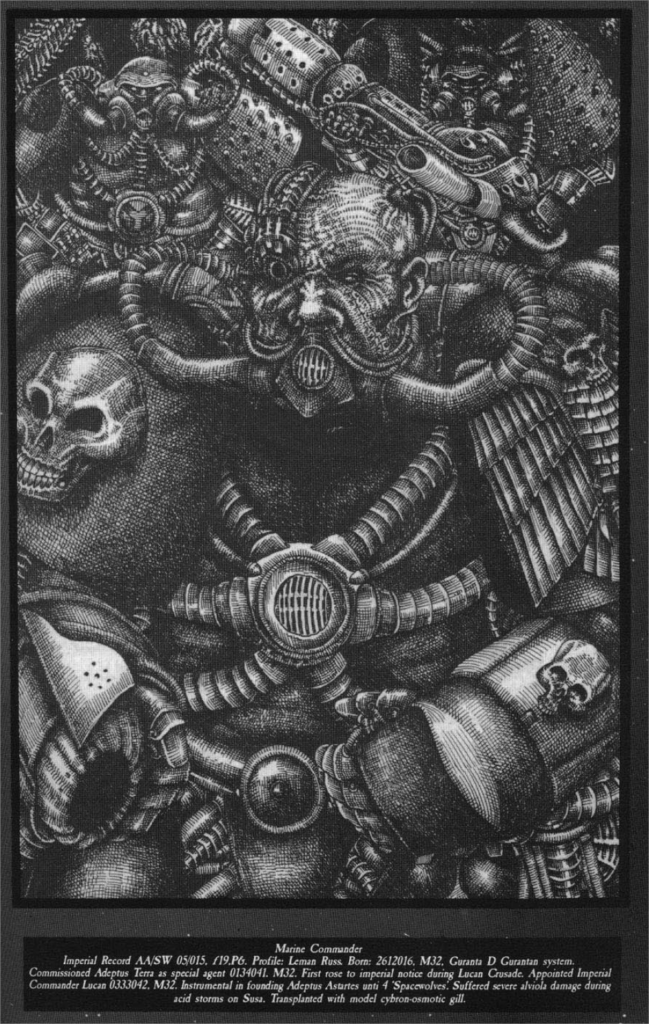

This is peak Leman Russ, as he should be:

Not this:

Warhammer 40,000, as depicted and conceived in the 80ies absolutely was a satire and reaction to Thatcherism in the UK, quite in line with comics like Judge Dredd and other things from the 2000 AD magazine. Space Marines were fucked up purposefully mutated humans that were fighting fucked up accidentally mutated humans.

And in that take of the universe, I think it is fine to have uber-macho all-male Space Marines, to have a devoted cult of the emperor, to have the humans shout „death to all xenos“. Because it is clear from the artwork alone that this is a fucked up world, full of fucked up decisions. No one in there looks or stands in for anyone in our real world, which is a neat thing to have when the game is about wholesale slaughter. (Of course, a lot of the „human factions“ take on decorations and themes from armies from our real-world past. But they are so exaggerated, that I don’t really think a matching and identification is possible.)

So, yes, I actually like this take. It brings me back to the 80ies, to crusty Punks and Hair Metal, to counterculture and rebellion.

But today, as the artwork starts to become squeaky clean and actually heroic. Games Workshop is clearly trying to focus on about how cool the Space Marines are. Nothing on the surface tells you that they would be fucked up, and the lore keeps telling you that they have to be the way they are, that the xenos threat is real.

And with that, the satire looses its teeth. Games Workshop of course knows this, so they end up having to make the good guys, you know, actually good. These toy soldiers cannot be doing warcrimes left and right anymore, they become more good-looking, and (and that is where the sad puppies start howling at the moon) you start making figures that your whole audience can identify with.

And that means including people of colour, a variety of gender being represented outside of Slaaneesh cults, and so on. Because the factions aren’t all villains anymore.

This change is the natural consequence of the slow-but-sure transition of the Space Marines from „crazed fanatics willing to die for the cult of a dead Emperor rotting on his golden throne“ to „somehow heroic, noble and virtuous. As good guys.“ (quotes from freethoughtblogs.com/pharyngul)

So, if you want the Space Marines and the Empire of Man to be „the good guys“, you have to embrace the good sides of humanity too. And that means including ALL of humanity, in all its multi-gendered, multi-skin-hues, multi-anything glory.Sorry to the sad puppies, I don’t make the rules, I’m just telling you how it is.